Uncovering the Untamed Side of Xinjiang Hetian Jade: A Deep Dive into Mariyan Gem Markets

I. Sourcing Authentic Hetian Jade

The Xinjiang Hetian Jade trading scene in Xinjiang, China, has its regulated centers like the Daqiao Bazaar and Zongzhakou gate—places for standardized rough jade transactions. However, seasoned jade hunters often prefer venturing into the countryside to test their luck. My journey led me to Mariyan, a village that is truly the source, famous for producing stunning Mariyan jade (often referred to as Mariyan or Maria), especially those rough stones with vibrant, beautifully colored skins (pise liao).

Curiously, if you search for “Mariyan” or “Maria” on a map, you might only find a primary school and a gynecology hospital in Luopu County. To find this jade haven, you must take the Xisha Line from the Second Bridge, drive southeast for about 12 kilometers to Qiaerbage Village, turn left through a bridge underpass, and follow the asphalt country road north for seven kilometers. That’s how you arrive at Mariyan.

Locating the Mariyan Source: Market Locale and the Jade Hunters’ Quest

In the vicinity of Mariyan, you’ll find two smaller villages where you can also find stones—Ying’awati and Suyakumu—but their scale is insignificant. I won’t elaborate on them.

Visiting Mariyan without a local guide is nearly impossible. The excitement of jade hunters is palpable as they pass the sand and gravel plants fenced off with corrugated iron along the roadside. In this remote countryside, Han Chinese jade hunters resemble wandering martial arts masters (xia-ke). They may travel solo or in small groups of three to five, where their expertise in judging stones is their internal strength (neigong), and their haggling skills are their external maneuvers (zhaoshi). Equipped with sun-protective clothing and high-powered flashlights, they engage in intense negotiation battles with the sellers, or “adaxi”. When exhausted, they might rest briefly on a noodle stand bench, only to rise again and plunge back into the intense sunlight, tirelessly searching for the perfect piece of Xinjiang Hetian Jade.

Mariyan Trading Dynamics: Why Experienced Hunters Target this Raw Source

Mariyan usually has no more than ten adaxi selling stones. Although some of the stock has often been seen at the Daqiao Bazaar, jade hunters frequent Mariyan hoping to intercept the new, freshly unearthed materials that appear intermittently.

Whenever a nearby sand and gravel plant unearths jade stones, someone purchases them to sell in Mariyan. This new stock might be a couple of small pieces held in a peddler’s hand or hundreds of thousands of pieces of commercial-grade rough bulk (tonghuo) in a large container.

When news of a new batch of tonghuo hits Mariyan, adaxi from dozens of kilometers around rush in to get the first pick and negotiate prices. Often, one or two sellers must simultaneously handle intense price negotiations from over a dozen local adaxi. In this relatively closed environment, Han Chinese are noticeably excluded. The best stones usually go to the adaxi first, and prices are more easily negotiated between Uighur sellers.

When you manage to push into the crowd, snag a good stone, and offer a standard low price, the seller often impatiently waves you off, feeling you are wasting their time. However, if you are a big spender—an outsider willing to pay high, perhaps foolish prices—you will be warmly welcomed here.

Navigating the Risks: The Price of the Untamed Xinjiang Jade Market

Naturally, not every new batch of material proves breathtaking; disappointment is the norm. Because Mariyan functions as a small-scale village trading post, it completely lacks the security checks and armed police presence found at the Daqiao Bazaar. Consequently, this absence of security sometimes allows for more aggressive behavior from certain local Uighur individuals.

A Confrontation at the Trading Post

I experienced this firsthand while negotiating for a stone. I offered 23,000 RMB, and the seller dropped his minimum to 25,000 RMB. Just as we were nearing a deal, a Uighur bystander suddenly intervened, trying to position himself as a middleman. Although I politely declined his assistance, he persisted relentlessly. The stone finally sold for 25,000 RMB, and the seller effectively snubbed the impromptu middleman, giving him no cut.

Following the sale, the man immediately asked to see the stone I had just bought. Once he had it, he refused to let go, loudly yelling that he was going to auction it off. A crowd of adaxi quickly gathered. I told him clearly, “I have paid the money. The stone is now mine. I am not auctioning it.”

Standing Firm Against Extortion

When his disruption failed, he brazenly escalated his demands, insisting on 300 RMB as a commission for his “help” and threatening to withhold the stone otherwise.

I responded decisively, “I bought the stone for 25,000 RMB. You have absolutely nothing to do with this transaction.”

“You give me 300 RMB, and I give you the stone!” he insisted aggressively.

“Impossible!”

He then resorted to a threat: “(Ah Nange Si Ge, a Uighur curse). Don’t you want to leave today if you don’t pay?”

I met his challenge directly. I pointed at his chest, locked eyes with him, and deliberately stated, “Give me the stone, or you won’t be leaving today either!” Perhaps realizing he was in the wrong, the middleman eventually released the stone, muttering curses as he walked away.

The Lesson in Bravery

It is important to remember: While safety is always a concern when hunting for rough material in remote regions, you absolutely should not tolerate such thuggish behavior. The Uighur people are a culture that respects bravery. If you compromise with a local bully’s aggression, even the surrounding adaxi will look down on you.

II. The Pedigree of Xinjiang Hetian Jade: Understanding the ‘Race’ and ‘Age’ of Seed Jade (Ziyu)

Just as different people come from different backgrounds, a single river nourishes thousands of types of stones. Have you ever considered that even within the same Hetian seed jade (Ziyu) sourced from the Yulongkashi River, they possess characteristics that define their “race” and “age”?

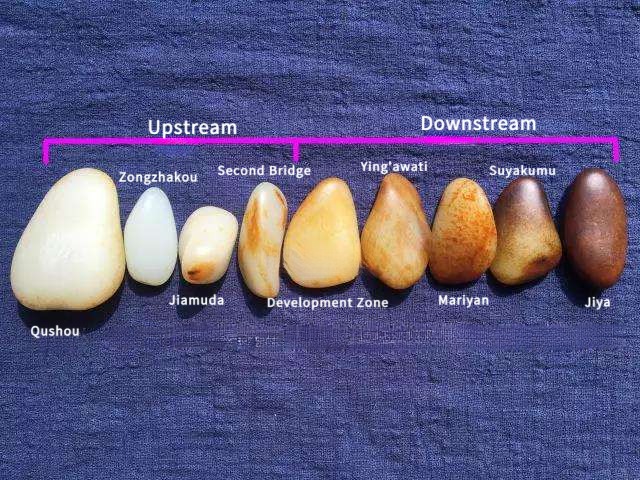

Experienced jade hunters working along the Yulong River know that the “race” of the Ziyu—meaning the distinct characteristics of the stones—varies by river segment.

- The upper reaches, near the Qushou (diversion dam), mainly produce stones with white skin (bai pi liao).

- The Zongzhakou and Jiamuda segments mostly yield pure smooth white seed jade (guang bai zi) or those with a thin layer of red oil skin (hong you pi).

- The downstream areas, like Mariyan and Suyakumu, are rich in diffusion-stained jade (qin liao) and those with deeply colored skins.

The image provided clearly illustrates the typical characteristics of Hetian seed jade (Ziyu) sourced from different segments of the Yulongkashi River, where each piece exhibits the hallmark traits of the material originating from that specific river section. While these traits are not absolute and often overlap, the chart represents the general pattern: The jade’s skin color progresses from light to dark as you move downstream: white skin → smooth white → red skin → black skin.

The Geological Roots: How River Environment Determines Ziyu Color and Appearance

No one has conclusively explained the reason for these “racial” differences in Ziyu. Zilongzhai suggests the answer lies in understanding how the seed jade formed. The mainstream view holds that when jade mountain material breaks off, the Yulongkashi River tumbles and polishes the material over long periods, thereby forming Ziyu as a secondary deposit. However, a more recent, compelling theory, which scholars like Mr. Jiang Youru support, posits that volcanic magma eruptions formed Ziyu as a primary deposit when the Xinjiang region was still an ocean floor.

Regardless of the “Primary” vs. “Secondary” debate, a consensus remains: the formation of Ziyu was significantly influenced by the geological environment of the Yulong River.

By looking at a satellite map of the Yulongkashi River, we can visually grasp the terrain. The river flows north from the Kunlun Mountains, and the jade-producing areas are concentrated along both banks of the river channel, spanning upstream and downstream of Hotan City. The gray strips are the riverbeds; the green areas are farmland; and the yellowish-gray parts are the main mining fields.

From the large fields on both sides of the Qushou, to the completely forbidden-to-mine Jiamuda, to the increasing output in the Development Zone, and finally to the sand and gravel fields between Jiye Village and Mariyan—each area has a different geological composition. The ancient river channels and deep soils have varying mineral content. Downstream areas, with higher concentrations of mineral elements, experience more intense staining of the Ziyu by the water and soil, resulting in the rich, deep colors of the jade skin. This is merely a personal theory based on observation, intended for thought-provoking discussion, leaving the final proof to geological professionals.

Understanding Ziyu’s ‘Age’ and Maturity

Recognizing the Ziyu‘s “race” helps in understanding its formation but offers little practical value when hunting for stones. It simply gives you a rough idea of its origin. What is far more important is the jade’s “age”—the degree of its maturity or development, influenced by congenital and acquired factors.

You’ve likely heard terms like “old and mature jade quality” (yuzhi laoshu), “old pit material” (lao keng liao), and “old skin” (lao pizi). These all evaluate a Ziyu‘s maturity.

PeonyJewels believes the age of the Ziyu is primarily reflected in four aspects:

1. Shape and Form

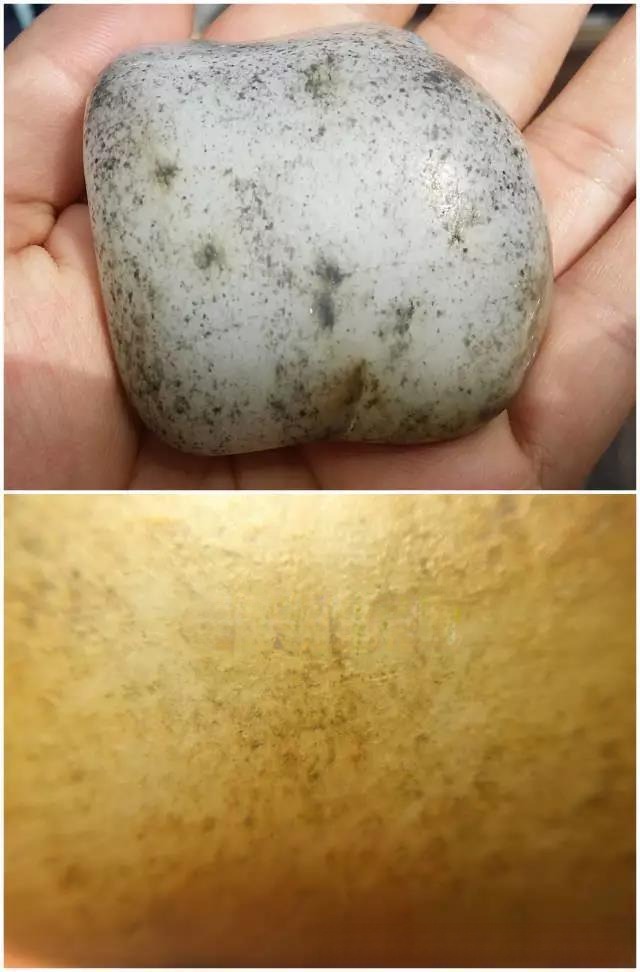

Through geological movement and river erosion, all Ziyu tends toward smooth, round shapes. No matter how unusual its initial form, the external environment will eventually wear away its edges. The smooth, rounded stone (right) is considered “mature” compared to the oddly shaped stone (left), which recently broke off from a larger chunk. This roundness, therefore, directly measures the time the water spent tumbling and polishing the stone.

2. Skin Color (Pise)

An industry saying, “A thousand years for red, ten thousand years for black,” describes the developmental process of the Ziyu skin. Skin formation requires millennia of mineral infiltration. When we dig it up, its natural growth is frozen.

Recently, the “Oil Tank Skin” (youku pi) appeared on the market, initially dismissed as fake by many due to its unfamiliar look. As shown in the image, similar black, pinpointed skins exist at the base of many red, black, and russet skins. This suggests that the Oil Tank Skin might be an intermediate developmental stage. If its growth hadn’t been interrupted, would it eventually evolve into a different, more familiar skin color? The skins we see are at various stages of development—some newly formed, others fully mature. If we compare mineral infiltration to life’s trials, the stones that have experienced more trials are more mature, giving the downstream stones their look of “world-weary” color.

To understand common market deceptions, especially those involving the artificial coloring of jade skin, see our related PeonyJewels blog article: The Truth Behind “Miracle Whitening” and Other Hetian Jade Forgery Techniques.

3. Surface Pores (Maokong)

Due to variations in formation time and space, the intensity and duration of the external polishing on Ziyu also differ, leading to “new” and “old” pores.

For jade of the same quality, stones tumbled more by the river generally have uniform and fine pores. Stones found in land or desert-edge deposits, however, may have coarse and rough pores. As shown in the image, these are the so-called “dry seed” (han zi), “dry pit material” (gan keng liao), or “sand-returned-to-water” (shui fan sha). The river’s polishing gives a stone a familiar, smooth, and tactilely pleasing shell.

A key difference is the oiliness and smoothness. An “old stone,” having been out of the river longer and handled, is often naturally smoother and oilier. A “new stone,” fresh from the river and unpolished, can feel rough to the touch. With prolonged handling (playing), the pores on an “old stone” may even become faint, nearly disappearing. Uniform and fine pores are considered more mature than coarse, raw ones.

4. Jade Quality (Yuzhi)

The age of the jade quality is defined by its fineness (xidu) and glutinousness (nuoxing).

- The tremolite content determines the quality of the fineness. High tremolite content leads to fine, yellowish-greenish stones, giving a dense, mature visual texture. Low content results in a loose, pale appearance.

- The interlacing structure determines the quality of the glutinousness. High interlacing structure gives the stone a thick, dense, and mature glutinous feel (hunhou shunu zhi gan). Low interlacing results in a watery, clear feel.

A Ziyu that exhibits both excellent fineness and glutinousness is called a “fully mature material” (laoshu liao). Conversely, we consider stones lacking these qualities to be “young.” Crucially, we believe that fineness and glutinousness are innate—they result from the initial formation, and the river does not “soak” them into the jade. A dry, low-quality Kawaste stone will never evolve into Ziyu no matter how long it soaks.

The Importance of Recognizing Ziyu’s Diversity

There is no inherent better or worse among the different “races” and “ages” of Hetian Ziyu (seed jade). The primary takeaway is the immense diversity of seed jade. Many enthusiasts and even jade dealers haven’t seen enough varieties of rough Xinjiang Hetian Jade. This limited exposure often leads to misconceptions:

- Many still only recognize the smooth white seed jade and concentrated red skin from the river’s upper reaches.

- They mistake the iron-rust spot skin for secondary enhancement (artificially stained jade).

- They equate coarse, irregular pores with tumbling in a cement mixer.

- They stubbornly believe that only “oil skin” is authentic, labeling all skins that have diffused deep into the jade flesh (qin pi) as fake coloring.

These limited views stem from a lack of exposure to the jade’s true diversity.If you are looking to become a discerning collector and learn how to separate authentic Ziyu from its natural look-alikes, consult our detailed expert guide: The Nephrite Deception: Your Expert Guide to Authentic Hetian Jade and Its Natural Imposters.

Case Study: Understanding the Young Ziyu from Qushou

I once examined a stone from the Qushou area. Its young age meant its shape still held some faint edges, not yet perfectly round. Its desert-edge geological environment gave it the coarse, raw pores of a “dry pit material.” The skin was just a thin layer of light gold sprinkle. Many assumed this was a fake because the shape, pores, and thin skin were unfamiliar.

However, a closer look at the flow lines of the shape and the chaotic, natural distribution of the pores confirmed it was formed by natural forces. The light skin was simply due to its young developmental age, lacking multi-layered accumulation. Crucially, its fissures had no color buildup, the breaks held alkali soil, and the white, stiff parts (bai jiang) remained white and unstained—a piece that raised suspicion at first glance but was clearly authentic upon closer inspection.

Final Wisdom: Seeing Beyond the Misconceptions

Light skin is not necessarily fake, nor are strange pores necessarily artificial. In fact, artificially sandblasted pores are often too uniform. By considering the upper Qushou’s geological characteristics and the stone’s developmental “age,” one can understand why this “young Ziyu” was so unique.

As the adaxi wisely put it: “Stones in the river, there are many forms. Only God knows them!” (“He li de shitou ma, yangzi duo ne, zhiyou Hu Da zhidao ne!”)

The older Xinjiang Hetian Jade sellers in Mariyan have a serene look, like a stone fully polished by life’s trials—smooth, round, and filled with deep contemplation. They embody the realization that life, like the appreciation of Xinjiang Hetian Jade, is a journey of understanding.

III. Conclusion: A Call for Wisdom and Discovery in the World of Jade

The journey to Mariyan is a pilgrimage to the raw, untamed heart of the Xinjiang Hetian Jade supply chain. It is a place of high risk and high reward, where courage and knowledge are your most valuable currency. It teaches that the value of jade is not just in its color or texture, but in its provenance, its unique geological history, and its age of maturity. Just as the ancient sages described three stages of enlightenment—seeing mountains as mountains, then not as mountains, and finally seeing them as mountains again—the Xinjiang Hetian Jade collector progresses from novice enthusiasm to cynical skepticism, and finally to a knowledgeable, holistic appreciation of authenticity and diversity.

This raw experience of connecting with the source material—understanding the race and age of Ziyu—is what truly defines a seasoned collector.

✨ From Raw Stone to Refined Art: The PeonyJewels Customization Experience

At PeonyJewels, we bring the wisdom learned from these remote sourcing journeys into our craft. We honor the character and history of materials, much like the aged texture of a mature Xinjiang Hetian Jade.

Are you looking to capture the timeless elegance of the ancients with a touch of modern flair?

- Customization Service: We offer PeonyJewels bespoke jewelry services, using the finest materials to translate your vision into a unique, wearable masterpiece.

- Original Designs: Explore our collection of original handmade vintage earrings. Each piece is a testament to quality, designed to possess enduring beauty and depth, perfect for celebrating everyday elegance.

Step into the world of truly meaningful jewelry. Visit PeonyJewels today to start your bespoke journey or find your next timeless piece.